Old high-bunker becomes a modern residential quarter

In Düsseldorf architect David Wodtke has converted a high bunker from the Second World War into a modern, sustainable building complex with flats and commercial space.

Historical building fabric and 21st century energy technology

In Düsseldorf architect David Wodtke has converted a high bunker from the Second World War into a modern, sustainable building complex with flats and commercial space. Thanks to a photovoltaic system, E3/DC electricity storage and a combined heat and power unit, around 95 percent of the electricity demand, including for electric mobility, can be covered independently of the energy supplier. The tenants benefit from cheap electricity.

It takes a lot of imagination to imagine a dilapidated bunker from the Second World War as a modern, sustainable building for affordable and communal living and working. David Wodtke already had this vision as a student in Berlin, where the Friedrichstraße high-rise bunker gave him the idea. Even when he returned home to North Rhine-Westphalia in 2018, he could not let go of this idea. In the Gerresheim district of Düsseldorf he found a high bunker built in 1942. There the architect wanted to realise his dream and show how to make a historic building fit for the 21st century. In spring 2021, the renovated building complex with two additional storeys and a new annex was ready for occupancy. The energy concept with photovoltaic system, E3/DC electricity storage systems and a combined heat and power (CHP) unit ensures that 95 per cent of the electricity demand can be covered independently of the energy supplier. Private and commercial tenants save energy costs through low-cost tenant electricity and tenant heat.

The high bunker opposite the “Neustadt” workers’ housing estate was part of the Gerresheim glassworks. Both are remnants of the Second World War. Since demolishing the bunker would have been too expensive, the grey concrete complex stood unused for decades – except for a discotheque, a betting office and an illegal hemp plantation within its walls.

The CHP unit has a thermal output of around 40 kW and an electrical output of 20 kW.

Owner David Wodtke has added two storeys and created a spacious living area with lots of glass.

The E3/DC Home power stations store electricity from the PV system and the CHP unit with a total capacity of 52 kilowatthours.

The photovoltaic system with 60 kilowatts of power found its place on the new building.

The CHP unit has a thermal output of around 40 kW and an electrical output of 20 kW.

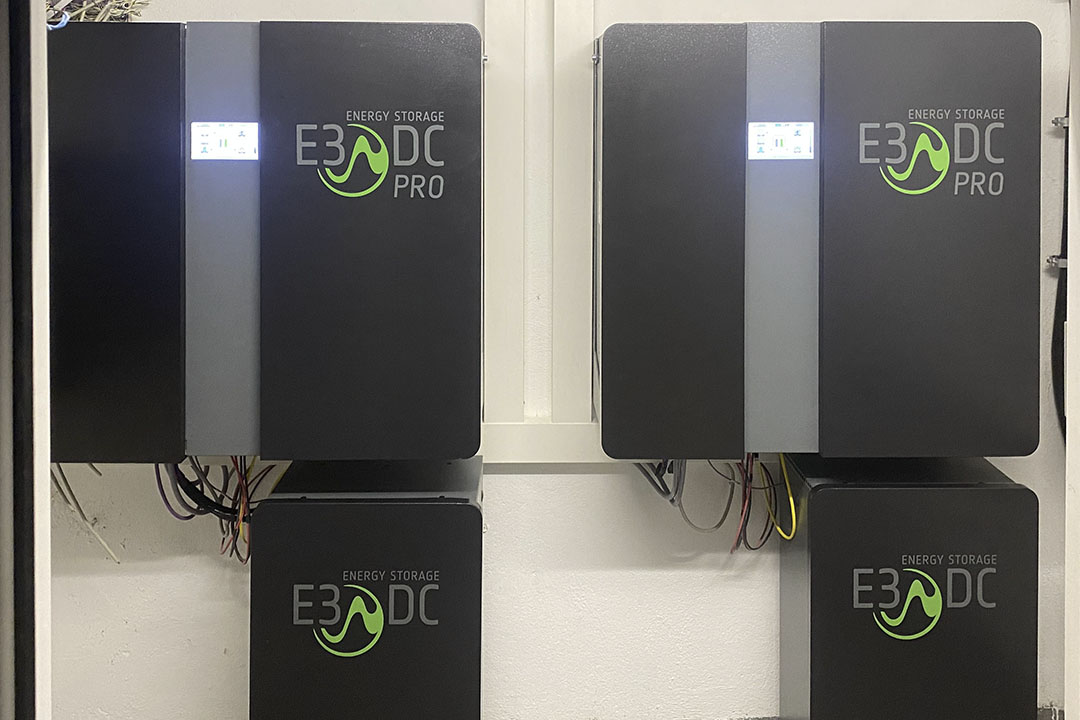

Assembly of the two E3/DC Home power stations of the PRO series in the former high bunker

Creating affordable housing

David Wodtke thought that the historic building could and should be put to better use, especially when flats are scarce and expensive in a city like Düsseldorf. “I wanted to create living space for myself and others, build sustainably and the energy should be generated as locally as possible.” This is how he outlines his goals for the ambitious building project.

Most bunkers in Germany belong to the federal government. Wodtke’s high bunker was privately owned, and he bought it six months after his return. There were no problems with the permits for the building project. “We have a great building authority in Düsseldorf,” the 38-year-old emphasises. The building authorities preferred his plans for use, including the social facilities, rather than a disco or a betting office.

The first big task was to bring light into the interior. Windows are not provided in bunkers, so holes had to be made in the thick walls.

Versatile use

While Wodtke itself was planning the reconstruction and the annex, Matthias Henkel, managing director of the company Congy – Concepts for Energy from Kevelaer, developed the energy concept for the heat and power supply. The intended usage was the basis for the innovative regenerative energy concept.

In addition to the old bunker Wodtke has built an extension. In total, there are 4,500 square metres of heated space. This is how the area is used: The ground floor houses a day-care centre and an organic snack bar. The co-working space is currently vacant due to the Corona pandemic, but is to be rented out as soon as possible. The day care centre also uses the first floor. On the second, third and fourth floors is space for so-called sibling living. Here children and young people who have been taken from their families can live together. On these floors there are also large flats for families. On the fifth and sixth floor are more expensive flats. The seventh floor is occupied by the owner himself, and on the eighth floor he has set up his office. The top two floors were built on top of the old bunker. In total 28 residential units for about 90 people have been created, plus the commercial areas.

Wodtke has also set up an indoor playground in the bunker basement. In an area of 300 square metres of space, the young people from the house can do sports.

Energy concept with photovoltaics, storage and CHP unit

The architect, together with Congy, calculated the electricity requirement, including electromobility, at 155,000 kilowatt hours per year (120,000 kWh of kWh building consumption and 35,000 kWh e-mobility). Matthias Henkel of Congy recommended the combination of a photovoltaic system, E3/DC Home power stations and a combined heat and power unit (CHP) for electricity and heat supply. The building owner liked the proposal. “This is a haptic model, so to speak. We can show our tenants where the energy is produced.”

This is already visible from the outside. On the new extension the Congy company installed solar power modules with an output of 60 kilowatts. According to calculations, the system will produce around 60,000 kilowatt hours of electricity per year. Henkel has combined it with two E3/DC Home power stations from the PRO series. They have a total storage capacity of 52 kilowatt-hours and store solar power temporarily when it cannot be consumed directly.

Retrofittable electricity storage in farming operation

A special feature of the energy concept is the farming operation of the storage systems of the PRO series. This means that the two storage units are connected in parallel to form an intelligent “energy farm” and only have one connection to the public power grid. One storage unit acts as the “master” or “farm manager” and is connected to the grid control point. It communicates with the other storage unit, the “slave”, via the network or the internet.

If the storage capacity needs to be increased in time, this is no problem with the E3/DC storage systems. However, Wodtke wants to wait for the first interim results and then, if necessary, upgrade the storage capacity.

CHP generates heat and electricity

The combined heat and power unit with a thermal output of approximately 40 kilowatts and 20 kilowatts electrical output produces around 226,000 kilowatt hours of heat and 116,000 kilowatt hours of electricity per year. For the operation of the CHP 355,000 kilowatt hours of natural gas is needed per year. With a significantly higher efficiency than large-scale power plants, the CHP unit generates heat and electricity. When the solar power from the photovoltaic system on the roof is not sufficient, electricity from the CHP unit is used in the building. It can be temporarily stored in the E3/DC Home power stations. The surplus from both the PV system and the CHP unit is fed into the public grid.

Of the approximately 176,000 kilowatt hours of electricity that are generated on and in the high bunker, 75 per cent can be consumed directly, according to the simulation. Of the total electricity consumption, 95 per cent is consumed locally and independent of the energy supplier. Only about five percent will be drawn from the grid. In addition to these systems, an adsorption chiller has been installed. “In the summer, it uses surplus heat from the CHP unit and converts it into cooling for the offices,” Henkel explains.

Ecological building materials

In order to reduce the heat requirement, Wodtke attached a 160-millimetre thick mineral wool insulation on the exterior walls. “The walls are extremely thick and it is a lot of storage mass, however, thanks to the insulation we can be sure that the temperature in the building will remain constant throughout the year,” he explains. He has estimated the heat demand in the building at 50 kWh per square metre and year. If the heat from the CHP is not sufficient, a gas-fired peak-load boiler kicks in.

It was important to the owner to build as ecologically as possible. Therefore he did not use polystyrene, for example, and uses wood wool for insulation in the drywalls. On the roof he had to use glass wool. Where possible, plastering was done with clay.

Saving energy costs with tenant electricity

The architect offers his private and commercial tenants so-called tenant electricity. Wodtke had to set up a limited company for this purpose. The technical processing and billing is handled by Congy. The tenant electricity price is one cent below the green electricity tariff of the local utility and approximately 2.6 cents below the price for conventional electricity. Tenants are free to decide whether they want to use tenant electricity or whether they want to buy power from the energy supplier. So far the price advantage has convinced everyone.

The same applies to the heat supply. David Wodtke sells the heat from the CHP unit to his tenants. The heat price is about 5 per cent below that of the local supplier, again a convincing argument. Electromobility is also part of the energy concept. 12 E3/DC wall boxes are currently installed in the underground car park. Perhaps public charging stations will be added in the outdoor area.

The construction project has already made headlines at the start of 2019. And so the flats were in demand. “Within a week they were rented out,” says David Wodtke. He had only advertised two.

In addition to the sensational building project – a historical bunker in a modern guise – and the extremely appealing appearance today the rent is also attractive. Wodtke charges an average of 14 euros per square metre of living space. That is four to five euros less than in the neighbourhood in the Gerresheim district, which is on the outskirts of Düsseldorf. By selling electricity and heat, he has additional profits. “Renewable energies have made that possible,” he says. “We show that old buildings with ancient substance can be brought into the 21st century. A new chapter has opened for grand old buildings.”